Kubernetes Brain Dump (ALWAYS WIP)

- Linux Network Namespaces is one of the important feature in Linux Kernel that are leveraged by containers like docker and kubernetes. It is used in the CNI (Container Network Interface).

- A Kubernetes cluster can be deployed on either physical or virtual machines.

- Once you’ve created a Deployment, the Kubernetes master schedules mentioned application instances onto individual Nodes in the cluster.

- Once the application instances are created, a Kubernetes Deployment Controller continuously monitors those instances. If the Node hosting an instance goes down or is deleted, the Deployment controller replaces the instance with an instance on another Node in the cluster. This provides a self-healing mechanism to address machine failure or maintenance.

- Node - A node is a VM or a physical computer that serves as a worker machine in a Kubernetes cluster.

- Each node has a Kubelet, which is an agent for managing the node and communicating with the Kubernetes master. The node should also have tools for handling container operations, such as Docker or rkt.

- A Kubernetes cluster that handles production traffic should have a minimum of three nodes.

- The nodes communicate with the master using the Kubernetes API. End users can also use the Kubernetes API directly to interact with the cluster.

Node Components run on every node, maintaining running pods and providing the Kubernetes runtime environment.

kubelet - An agent that runs on each node in the cluster. It makes sure that containers are running in a pod. The kubelet takes a set of PodSpecs that are provided through various mechanisms and ensures that the containers described in those PodSpecs are running and healthy. The kubelet doesn’t manage containers which were not created by Kubernetes.

kube-proxy - kube-proxy is a network proxy that runs on each node in your cluster, implementing part of the Kubernetes Service concept. kube-proxy maintains network rules on nodes. These network rules allow network communication to your Pods from network sessions inside or outside of your cluster. kube-proxy uses the operating system packet filtering layer if there is one and it’s available. Otherwise, kube-proxy forwards the traffic itself.

Container Runtime - The container runtime is the software that is responsible for running containers.

A node is a worker machine in Kubernetes, previously known as a minion. A node may be a VM or physical machine, depending on the cluster. Each node contains the services necessary to run pods and is managed by the master components.

A node’s status contains the following information:

- Addresses

- Conditions

- Capacity and Allocatable

- Info

Node

- Currently, there are three components that interact with the Kubernetes node interface: node controller, kubelet, and kubectl.

- Node Controller

- The node controller is a Kubernetes master component which manages various aspects of nodes.

- Assigning a CIDR block to the node when it is registered (if CIDR assignment is turned on).

- Keeping the node controller’s internal list of nodes up to date with the cloud provider’s list of available machines. When running in a cloud environment, whenever a node is unhealthy, the node controller asks the cloud provider if the VM for that node is still available. If not, the node controller deletes the node from its list of nodes.

- The node controller is responsible for updating the NodeReady condition of NodeStatus to ConditionUnknown when a node becomes unreachable (i.e. the node controller stops receiving heartbeats for some reason, for example due to the node being down), and then later evicting all the pods from the node (using graceful termination) if the node continues to be unreachable. (The default timeouts are 40s to start reporting ConditionUnknown and 5m after that to start evicting pods.) The node controller checks the state of each node every –node-monitor-period seconds.

- Node Controller

Pod

- Pod is something logical and not physical. It is just a logical wrapper for a set of containers with it’s resources. In terms of Docker constructs, a Pod is modelled as a group of Docker containers with shared namespaces and shared filesystem volumes.

- Containers within a Pod share an IP address and port space, and can find each other via localhost. They can also communicate with each other using standard inter-process communications like SystemV semaphores or POSIX shared memory. Containers in different Pods have distinct IP addresses and can not communicate by IPC without special configuration. These containers usually communicate with each other via Pod IP addresses.

- A Pod is a group of one or more containers (such as Docker containers), with shared storage/network, and a specification for how to run the containers.

- A Pod is a Kubernetes abstraction that represents a group of one or more application containers (such as docker or rkt), and some shared resources for those containers. Those resources include:

- Shared storage, as Volumes

- Networking, as a unique cluster IP address

- Information about how to run each container, such as the container image version or specific ports to use

- The containers in a Pod share an IP Address and port space, are always co-located and co-scheduled, and run in a shared context on the same Node.

A Pod always runs on a Node

- A Node is a worker machine in Kubernetes and may be either a virtual or a physical machine, depending on the cluster.

- Each Node is managed by the Master.

- A Node can have multiple pods, and the Kubernetes master automatically handles scheduling the pods across the Nodes in the cluster.

- The Master’s automatic scheduling takes into account the available resources on each Node.

Every Kubernetes Node runs at least:

- Kubelet, a process responsible for communication between the Kubernetes Master and the Node; it manages the Pods and the containers running on a machine.

- A container runtime (like Docker, rkt) responsible for pulling the container image from a registry, unpacking the container, and running the application.

Containers should only be scheduled together in a single Pod if they are tightly coupled and need to share resources such as disk.

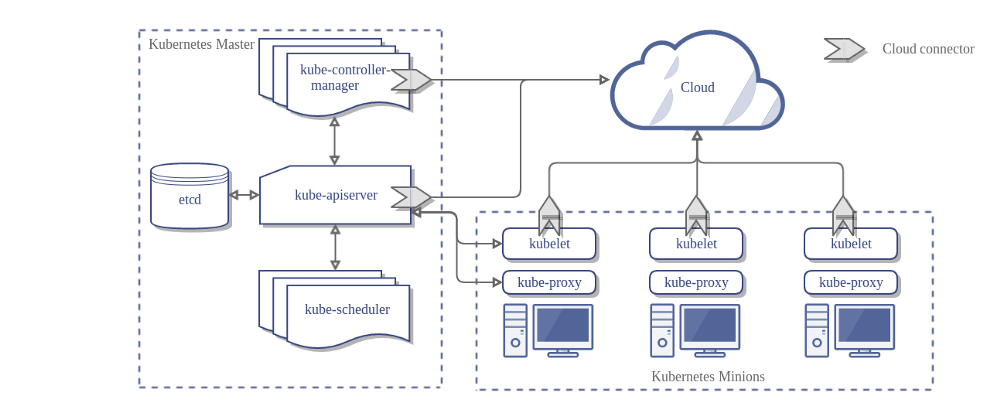

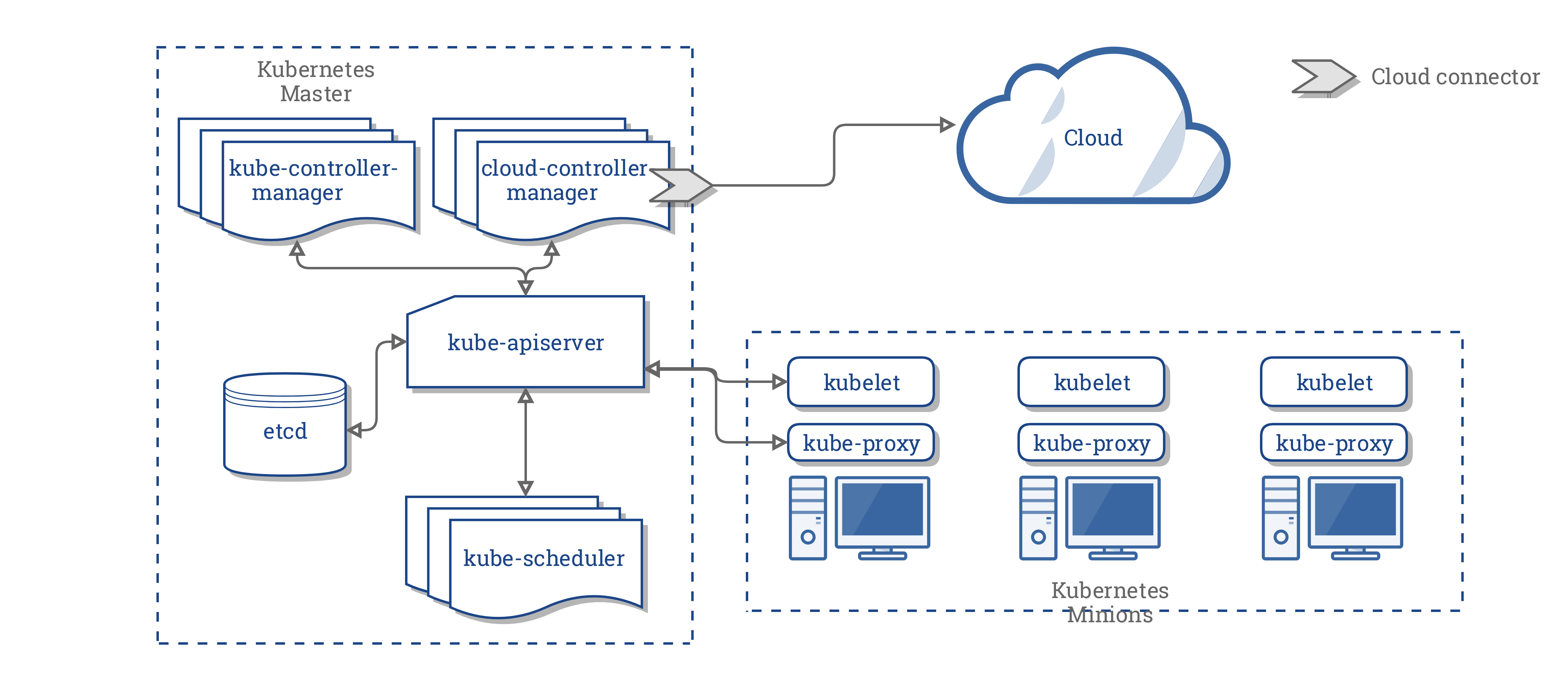

The Kubernetes Master is a collection of three processes that run on a single node in your cluster, which is designated as the master node. Those processes are: kube-apiserver, kube-controller-manager and kube-scheduler.

- Each individual non-master node in your cluster runs two processes:

- kubelet, which communicates with the Kubernetes Master.

- kube-proxy, a network proxy which reflects Kubernetes networking services on each node.

- Each individual non-master node in your cluster runs two processes:

Pod Lifecycle

- Container probes

- A Probe is a diagnostic performed periodically by the kubelet on a Container. To perform a diagnostic, the kubelet calls a Handler implemented by the Container.

- ExecAction: Executes a specified command inside the Container. The diagnostic is considered successful if the command exits with a status code of 0.

- TCPSocketAction: Performs a TCP check against the Container’s IP address on a specified port. The diagnostic is considered successful if the port is open.

- HTTPGetAction: The diagnostic is considered successful if the response has a status code greater than or equal to 200 and less than 400.

- The kubelet can optionally perform and react to three kinds of probes on running Containers:

- livenessProbe: Indicates whether the Container is running. If the liveness probe fails, the kubelet kills the Container, and the Container is subjected to its restart policy. If a Container does not provide a liveness probe, the default state is Success.

- readinessProbe: Indicates whether the Container is ready to service requests. If the readiness probe fails, the endpoints controller removes the Pod’s IP address from the endpoints of all Services that match the Pod. The default state of readiness before the initial delay is Failure. If a Container does not provide a readiness probe, the default state is Success.

- startupProbe: Indicates whether the application within the Container is started. All other probes are disabled if a startup probe is provided, until it succeeds. If the startup probe fails, the kubelet kills the Container, and the Container is subjected to its restart policy.

- A Probe is a diagnostic performed periodically by the kubelet on a Container. To perform a diagnostic, the kubelet calls a Handler implemented by the Container.

- Use different kind of pods for different kind of usage:

- Use a Job for Pods that are expected to terminate, for example, batch computations. Jobs are appropriate only for Pods with restartPolicy equal to OnFailure or Never.

- Use a ReplicationController, ReplicaSet, or Deployment for Pods that are not expected to terminate, for example, web servers. ReplicationControllers are appropriate only for Pods with a restartPolicy of Always.

- Use a DaemonSet for Pods that need to run one per machine, because they provide a machine-specific system service.

Init Containers

- A Pod can have one or more init containers, which are run before the app containers are started.

- Init containers are exactly like regular containers, except:

- Init containers always run to completion.

- Each init container must complete successfully before the next one starts.

- Kubernetes repeatedly restarts the Pod until the init container succeeds. However, if the Pod has a restartPolicy of Never, Kubernetes does not restart the Pod.

- Init containers support all the fields and features of app containers, including resource limits, volumes, and security settings.

- Init containers do not support readiness probes because they must run to completion before the Pod can be ready.

- If you specify multiple init containers for a Pod, Kubelet runs each init container sequentially. Each init container must succeed before the next can run. When all of the init containers have run to completion, Kubelet initializes the application containers for the Pod and runs them as usual.

- Example of defining init containers for a pod. The init containers will keep

apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: myapp-pod labels: app: myapp spec: containers: - name: myapp-container image: busybox:1.28 command: ['sh', '-c', 'echo The app is running! && sleep 3600'] initContainers: - name: init-myservice image: busybox:1.28 command: ['sh', '-c', "until nslookup myservice.$(cat /var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/namespace).svc.cluster.local; do echo waiting for myservice; sleep 2; done"] - name: init-mydb image: busybox:1.28 command: ['sh', '-c', "until nslookup mydb.$(cat /var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/namespace).svc.cluster.local; do echo waiting for mydb; sleep 2; done"] --- apiVersion: v1 kind: Service metadata: name: myservice spec: ports: - protocol: TCP port: 80 targetPort: 9376 --- apiVersion: v1 kind: Service metadata: name: mydb spec: ports: - protocol: TCP port: 80 targetPort: 9377

Pod Preset

- Kubernetes provides an admission controller (PodPreset) which, when enabled, applies Pod Presets to incoming pod creation requests.

- When a pod creation request occurs, the system does the following:

- Retrieve all PodPresets available for use.

- Check if the label selectors of any PodPreset matches the labels on the pod being created.

- Attempt to merge the various resources defined by the PodPreset into the Pod being created.

- On error, throw an event documenting the merge error on the pod, and create the pod without any injected resources from the PodPreset.

- Annotate the resulting modified Pod spec, the annotation is of the form podpreset.admission.kubernetes.io/podpreset-

: “ ”.

- Container probes

Controllers

ReplicaSet

- A ReplicaSet’s purpose is to maintain a stable set of replica Pods running at any given time. As such, it is often used to guarantee the availability of a specified number of identical Pods.

How a ReplicaSet works

- A ReplicaSet is defined with fields, including a selector that specifies how to identify Pods it can acquire, a number of replicas indicating how many Pods it should be maintaining.

- A ReplicaSet then fulfills its purpose by creating and deleting Pods as needed to reach the desired number. When a ReplicaSet needs to create new Pods, it uses its Pod template.

- A ReplicaSet identifies new Pods to acquire by using its selector.

- Example:

apiVersion: apps/v1 kind: ReplicaSet metadata: name: frontend labels: app: guestbook tier: frontend spec: # modify replicas according to your case replicas: 3 selector: matchLabels: tier: frontend template: metadata: labels: tier: frontend spec: containers: - name: php-redis image: gcr.io/google_samples/gb-frontend:v3

Make sure when declaring Pod kind: the metadata.labels.tier does not match the one in the ReplicaSet selector.matchLabels.tier field. If it does match the Pod will be obtained as part of the ReplicaSet. Look under Non-Template Pod acquisitions in for more info.

ReplicationController

- A ReplicationController ensures that a specified number of pod replicas are running at any one time. In other words, a ReplicationController makes sure that a pod or a homogeneous set of pods is always up and available.

- A ReplicationController is similar to a process supervisor, but instead of supervising individual processes on a single node, the ReplicationController supervises multiple pods across multiple nodes.

- A simple case is to create one ReplicationController object to reliably run one instance of a Pod indefinitely. A more complex use case is to run several identical replicas of a replicated service, such as web servers.

- Example:

apiVersion: v1 kind: ReplicationController metadata: name: nginx spec: replicas: 3 selector: app: nginx template: metadata: name: nginx labels: app: nginx spec: containers: - name: nginx image: nginx ports: - containerPort: 80

Deployments

- A Deployment provides declarative updates for Pods and ReplicaSets. The Deployment Controller changes the actual state to the desired state at a controlled rate.

- You can define Deployments to create new ReplicaSets, or to remove existing Deployments and adopt all their resources with new Deployments.

Example:

apiVersion: apps/v1 kind: Deployment metadata: name: nginx-deployment labels: app: nginx spec: replicas: 3 selector: matchLabels: app: nginx template: metadata: labels: app: nginx spec: containers: - name: nginx image: nginx:1.14.2 ports: - containerPort: 80Following are the explanation of the meaning of the above example:

- A Deployment named nginx-deployment is created, indicated by the .metadata.name field.

- The Deployment creates three replicated Pods, indicated by the replicas field.

- The selector field defines how the Deployment finds which Pods to manage. In this case, you simply select a label that is defined in the Pod template (app: nginx). However, more sophisticated selection rules are possible, as long as the Pod template itself satisfies the rule.

- The template field contains the following sub-fields:

- The Pods are labeled app: nginxusing the labels field.

- The Pod template’s specification, or .template.spec field, indicates that the Pods run one container, nginx, which runs the nginx Docker Hub image at version 1.14.2.

- Create one container and name it nginx using the name field.

To see the Deployment rollout status, run

kubectl rollout status deployment.v1.apps/nginx-deployment.To see the ReplicaSet (rs) created by the Deployment, run

kubectl get rsUpdating deployment:

Update the nginx Pods to use the nginx:1.16.1 image instead of the nginx:1.14.2 image.

kubectl --record deployment.apps/nginx-deployment set image deployment.v1.apps/nginx-deployment nginx=nginx:1.16.1or simply use the following command

kubectl set image deployment/nginx-deployment nginx=nginx:1.16.1 --recordAlternatively, you can edit the Deployment and change .spec.template.spec.containers[0].image from nginx:1.14.2 to nginx:1.16.1

kubectl edit deployment.v1.apps/nginx-deployment

Get details of your Deployment:

kubectl describe deploymentsFor example, suppose you create a Deployment to create 5 replicas of nginx:1.14.2, but then update the Deployment to create 5 replicas of nginx:1.16.1, when only 3 replicas of nginx:1.14.2 had been created. In that case, the Deployment immediately starts killing the 3 nginx:1.14.2 Pods that it had created, and starts creating nginx:1.16.1 Pods. It does not wait for the 5 replicas of nginx:1.14.2 to be created before changing course

Rolling Back a Deployment

Suppose that you made a typo while updating the Deployment, by putting the image name as nginx:1.161 instead of nginx:1.16.1:

kubectl set image deployment.v1.apps/nginx-deployment nginx=nginx:1.161 --record=trueThe rollout gets stuck. You can verify it by checking the rollout status:

kubectl rollout status deployment.v1.apps/nginx-deploymentRolling Back to a Previous Revision

kubectl rollout undo deployment.v1.apps/nginx-deployment

Scaling a Deployment

You can scale a Deployment by using the following command:

kubectl scale deployment.v1.apps/nginx-deployment --replicas=10Assuming horizontal Pod autoscaling is enabled in your cluster, you can setup an autoscaler for your Deployment and choose the minimum and maximum number of Pods you want to run based on the CPU utilization of your existing Pods.

kubectl autoscale deployment.v1.apps/nginx-deployment --min=10 --max=15 --cpu-percent=80

Pausing and Resuming a Deployment

Pause by running the following command:

kubectl rollout pause deployment.v1.apps/nginx-deploymentYou can make as many updates as you wish, for example, update the resources that will be used:

kubectl set resources deployment.v1.apps/nginx-deployment -c=nginx --limits=cpu=200m,memory=512MiEventually, resume the Deployment and observe a new ReplicaSet coming up with all the new updates:

kubectl rollout resume deployment.v1.apps/nginx-deployment

StatefulSets

- StatefulSet is the workload API object used to manage stateful applications. Manages the deployment and scaling of a set of Pods , and provides guarantees about the ordering and uniqueness of these Pods. Like a Deployment , a StatefulSet manages Pods that are based on an identical container spec. Unlike a Deployment, a StatefulSet maintains a sticky identity for each of their Pods. These pods are created from the same spec, but are not interchangeable: each has a persistent identifier that it maintains across any rescheduling.

StatefulSets are valuable for applications that require one or more of the following.

- Stable, unique network identifiers.

- Stable, persistent storage.

- Ordered, graceful deployment and scaling.

- Ordered, automated rolling updates.

Stable is synonymous with persistence across Pod (re)scheduling. If an application doesn’t require any stable identifiers or ordered deployment, deletion, or scaling, you should deploy your application using a workload object that provides a set of stateless replicas. Deployment or ReplicaSet may be better suited to your stateless needs

Example:

apiVersion: v1 kind: Service metadata: name: nginx labels: app: nginx spec: ports: - port: 80 name: web clusterIP: None selector: app: nginx --- apiVersion: apps/v1 kind: StatefulSet metadata: name: web spec: selector: matchLabels: app: nginx # has to match .spec.template.metadata.labels serviceName: "nginx" replicas: 3 # by default is 1 template: metadata: labels: app: nginx # has to match .spec.selector.matchLabels spec: terminationGracePeriodSeconds: 10 containers: - name: nginx image: k8s.gcr.io/nginx-slim:0.8 ports: - containerPort: 80 name: web volumeMounts: - name: www mountPath: /usr/share/nginx/html volumeClaimTemplates: - metadata: name: www spec: accessModes: [ "ReadWriteOnce" ] storageClassName: "my-storage-class" resources: requests: storage: 1GiExplanation about the above example:

- A Headless Service, named nginx, is used to control the network domain.

- The StatefulSet, named web, has a Spec that indicates that 3 replicas of the nginx container will be launched in unique Pods.

- The volumeClaimTemplates will provide stable storage using PersistentVolumes provisioned by a PersistentVolume Provisioner

Stable Network ID

- Each Pod in a StatefulSet derives its hostname from the name of the StatefulSet and the ordinal of the Pod.

- The pattern for the constructed hostname is $(statefulset name)-$(ordinal). The example above will create three Pods named web-0,web-1,web-2.

- A StatefulSet can use a Headless Service to control the domain of its Pods. The domain managed by this Service takes the form: $(service name).$(namespace).svc.cluster.local, where “cluster.local” is the cluster domain.

- As each Pod is created, it gets a matching DNS subdomain, taking the form: $(podname).$(governing service domain), where the governing service is defined by the serviceName field on the StatefulSet.

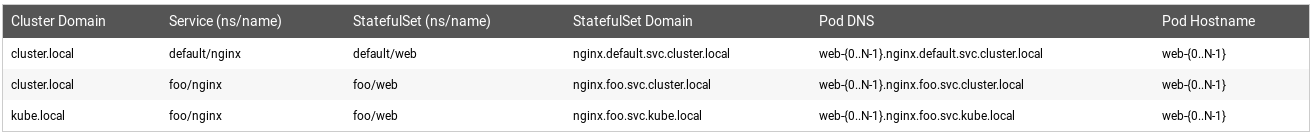

Here are some examples of choices for Cluster Domain, Service name, StatefulSet name, and how that affects the DNS names for the StatefulSet’s Pods.

Stable Storage

- In the nginx example above, each Pod will receive a single PersistentVolume with a StorageClass of my-storage-class and 1 Gib of provisioned storage.

- If no StorageClass is specified, then the default StorageClass will be used. When a Pod is (re)scheduled onto a node, its volumeMounts mount the PersistentVolumes associated with its PersistentVolume Claims.

- Note that, the PersistentVolumes associated with the Pods’ PersistentVolume Claims are not deleted when the Pods, or StatefulSet are deleted. This must be done manually.

Pod Name Label

- When the StatefulSet Controller creates a Pod, it adds a label, statefulset.kubernetes.io/pod-name, that is set to the name of the Pod. This label allows you to attach a Service to a specific Pod in the StatefulSet

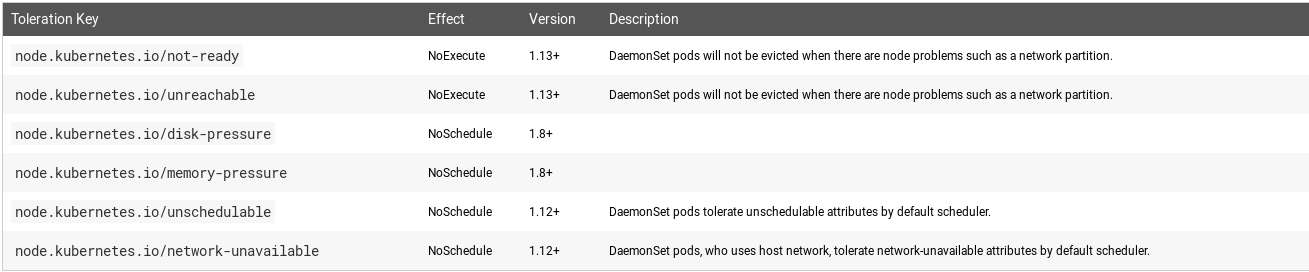

DaemonSet

- A DaemonSet ensures that all (or some) Nodes run a copy of a Pod. As nodes are added to the cluster, Pods are added to them. As nodes are removed from the cluster, those Pods are garbage collected. Deleting a DaemonSet will clean up the Pods it created.

- Some typical uses of a DaemonSet are:

- running a cluster storage daemon, such as glusterd, ceph, on each node.

- running a logs collection daemon on every node, such as fluentd or filebeat.

- running a node monitoring daemon on every node, such as Prometheus Node Exporter, Flowmill, Sysdig Agent, collectd, Dynatrace OneAgent, AppDynamics Agent, Datadog agent, New Relic agent, Ganglia gmond, Instana Agent or Elastic Metricbeat.

- In a simple case, one DaemonSet, covering all nodes, would be used for each type of daemon. A more complex setup might use multiple DaemonSets for a single type of daemon, but with different flags and/or different memory and cpu requests for different hardware types.

- Example:

apiVersion: apps/v1 kind: DaemonSet metadata: name: fluentd-elasticsearch namespace: kube-system labels: k8s-app: fluentd-logging spec: selector: matchLabels: name: fluentd-elasticsearch template: metadata: labels: name: fluentd-elasticsearch spec: tolerations: # this toleration is to have the daemonset runnable on master nodes # remove it if your masters can't run pods - key: node-role.kubernetes.io/master effect: NoSchedule containers: - name: fluentd-elasticsearch image: quay.io/fluentd_elasticsearch/fluentd:v2.5.2 resources: limits: memory: 200Mi requests: cpu: 100m memory: 200Mi volumeMounts: - name: varlog mountPath: /var/log - name: varlibdockercontainers mountPath: /var/lib/docker/containers readOnly: true terminationGracePeriodSeconds: 30 volumes: - name: varlog hostPath: path: /var/log - name: varlibdockercontainers hostPath: path: /var/lib/docker/containers How Daemon Pods are Scheduled

Scheduled by default scheduler

- A DaemonSet ensures that all eligible nodes run a copy of a Pod. Normally, the node that a Pod runs on is selected by the Kubernetes scheduler.

- However, DaemonSet pods are created and scheduled by the DaemonSet controller instead. That introduces the following issues:

- Inconsistent Pod behavior: Normal Pods waiting to be scheduled are created and in Pending state, but DaemonSet pods are not created in Pending state. This is confusing to the user.

- Pod preemption is handled by default scheduler. When preemption is enabled, the DaemonSet controller will make scheduling decisions without considering pod priority and preemption.

- ScheduleDaemonSetPods allows you to schedule DaemonSets using the default scheduler instead of the DaemonSet controller, by adding the NodeAffinity term to the DaemonSet pods, instead of the .spec.nodeName term.

- The default scheduler is then used to bind the pod to the target host. If node affinity of the DaemonSet pod already exists, it is replaced. The DaemonSet controller only performs these operations when creating or modifying DaemonSet pods, and no changes are made to the spec.template of the DaemonSet.

nodeAffinity: requiredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution: nodeSelectorTerms: - matchFields: - key: metadata.name operator: In values: - target-host-name

Taints and Tolerations

Services

- A Service in Kubernetes is an abstraction which defines a logical set of Pods and a policy by which to access them. Services enable a loose coupling between dependent Pods. A Service is defined using YAML (preferred) or JSON, like all Kubernetes objects. The set of Pods targeted by a Service is usually determined by a LabelSelector (see below for why you might want a Service without including selector in the spec).

Services can be exposed in different ways by specifying a type in the ServiceSpec:

- ClusterIP (default) - Exposes the Service on an internal IP in the cluster. This type makes the Service only reachable from within the cluster.

- NodePort - Exposes the Service on the same port of each selected Node in the cluster using NAT. Makes a Service accessible from outside the cluster using

: . Superset of ClusterIP. - LoadBalancer - Creates an external load balancer in the current cloud (if supported) and assigns a fixed, external IP to the Service. Superset of NodePort.

- ExternalName - Exposes the Service using an arbitrary name (specified by externalName in the spec) by returning a CNAME record with the name. No proxy is used. This type requires v1.7 or higher of kube-dns.

Services match a set of Pods using labels and selectors, a grouping primitive that allows logical operation on objects in Kubernetes. Labels are key/value pairs attached to objects and can be used in any number of ways:

- Designate objects for development, test, and production

- Embed version tags

- Classify an object using tags

Every node in a Kubernetes cluster runs a kube-proxy. kube-proxy is responsible for implementing a form of virtual IP for Services of type other than ExternalName

DNS

- For example, if you have a Service called “my-service” in a Kubernetes Namespace “my-ns”, the control plane and the DNS Service acting together create a DNS record for “my-service.my-ns”. Pods in the “my-ns” Namespace should be able to find it by simply doing a name lookup for my-service (“my-service.my-ns” would also work). Pods in other Namespaces must qualify the name as my-service.my-ns. These names will resolve to the cluster IP assigned for the Service.

- Kubernetes also supports DNS SRV (Service) records for named ports. If the “my-service.my-ns” Service has a port named “http” with the protocol set to TCP, you can do a DNS SRV query for _http._tcp.my-service.my-ns to discover the port number for “http”, as well as the IP address

Once you’ve set your desired state, the Kubernetes Control Plane makes the cluster’s current state match the desired state via the Pod Lifecycle Event Generator (PLEG). The Kubernetes Control Plane consists of a collection of processes running on your cluster:

- The various parts of the Kubernetes Control Plane, such as the Kubernetes Master and kubelet processes, govern how Kubernetes communicates with your cluster. The Control Plane maintains a record of all of the Kubernetes Objects in the system, and runs continuous control loops to manage those objects’ state. At any given time, the Control Plane’s control loops will respond to changes in the cluster and work to make the actual state of all the objects in the system match the desired state that you provided.

Master Components -Master components provide the cluster’s control plane. Master components make global decisions about the cluster (for example, scheduling), and they detect and respond to cluster events (for example, starting up a new pod when a deployment’s replicas field is unsatisfied). For simplicity, set up scripts typically start all master components on the same machine, and do not run user containers on this machine. See Building High-Availability Clusters for an example multi-master-VM setup.

kube-apiserver - Component on the master that exposes the Kubernetes API. It is the front-end for the Kubernetes control plane.

etcd - Consistent and highly-available key value store used as Kubernetes’ backing store for all cluster data.

kube-scheduler - Component on the master that watches newly created pods that have no node assigned, and selects a node for them to run on.

kube-controller-manager - Component on the master that runs controllers.

Logically, each controller is a separate process, but to reduce complexity, they are all compiled into a single binary and run in a single process. These controllers include:

- Node Controller: Responsible for noticing and responding when nodes go down.

- Replication Controller: Responsible for maintaining the correct number of pods for every replication controller object in the system.

- Endpoints Controller: Populates the Endpoints object (that is, joins Services & Pods).

- Service Account & Token Controllers: Create default accounts and API access tokens for new namespaces.

cloud-controller-manager - cloud-controller-manager runs controllers that interact with the underlying cloud providers. The cloud-controller-manager binary is an alpha feature introduced in Kubernetes release 1.6.

cloud-controller-manager runs cloud-provider-specific controller loops only. You must disable these controller loops in the kube-controller-manager. You can disable the controller loops by setting the –cloud-provider flag to external when starting the kube-controller-manager. cloud-controller-manager allows the cloud vendor’s code and the Kubernetes code to evolve independently of each other. In prior releases, the core Kubernetes code was dependent upon cloud-provider-specific code for functionality. In future releases, code specific to cloud vendors should be maintained by the cloud vendor themselves, and linked to cloud-controller-manager while running Kubernetes.

The following controllers have cloud provider dependencies:

[x] Node Controller – For checking the cloud provider to determine if a node has been deleted in the cloud after it stops responding

[x] Route Controller – For setting up routes in the underlying cloud infrastructure

[x] Service Controller - For creating, updating and deleting cloud provider load balancers

[x] Volume Controller - For creating, attaching, and mounting volumes, and interacting with the cloud provider to orchestrate volumes

Addons

Addons use Kubernetes resources (DaemonSet, Deployment, etc) to implement cluster features. Because these are providing cluster-level features, namespaced resources for addons belong within the kube-system namespace.

DNS - While the other addons are not strictly required, all Kubernetes clusters should have cluster DNS, as many examples rely on it. Cluster DNS is a DNS server, in addition to the other DNS server(s) in your environment, which serves DNS records for Kubernetes services. Containers started by Kubernetes automatically include this DNS server in their DNS searches.

Web UI (Dashboard) - Dashboard is a general purpose, web-based UI for Kubernetes clusters. It allows users to manage and troubleshoot applications running in the cluster, as well as the cluster itself.

Container Resource Monitoring - Container Resource Monitoring records generic time-series metrics about containers in a central database, and provides a UI for browsing that data.

Cluster-level Logging - Cluster-level logging mechanism is responsible for saving container logs to a central log store with search/browsing interface.

The basic Kubernetes objects include:

- Pod

- Service

- Volume

- Namespace

kubeadm

- Running ‘kubeadm init’ will run phases of initialization to setup Kubernetes cluster. The code that break down these steps reside inside app/cmd/phases/init

- preflight step reside inside app/preflight

- app/preflight/checks.go – contains lots of checking related to preflight (check port availability, check existence of directory, check app availability in PATH, etc)

- app/cmd/phases – these directory contains code that is tied to the different command line function in kubeadm (eg: phases/init –> has code that link to ‘kubeadm init’

- /init – directory contains code for all the phases when executing ‘kubeadm init’

- /join – directory contains code for the ‘kubeadm join’ command

- /reset – directory contains code for the ‘kubeadm reset’ command

- /upgrade – directory contains code for the ‘kubeadm upgrade’ command

- app/phases – contains code used as part of the kubeadm phases

- app/util/system

- cgroup_validator – validator for cgroups

- docker_validator – docker validator

- kernel_validator – kernel validator

- os_validator – OS validator (version)

- package_validator – package manager validator

CSI (Container Storage Interface)

- Interfacing K8 with storage implementation

- Node – A host where a workload (such as Pods in Kubernetes) will be running.

- Plugin - In the CSI world, this points to a service that exposes gRPC endpoints

- Specification defines the boundary between the CO and the CSI plugin.

- Plugin part actually is separated into two individual plugins.

- Node Plugin

- The Node plugin is a gRPC server that needs to run on the Node where the volume will be provisioned. So suppose you have a Kubernetes cluster with three nodes where your Pod’s are scheduled, you would deploy this to all three nodes.

- Controller Plugin

- The Controller plugin is a gRPC server that can run anywhere. In terms of a Kubernetes cluster, it can run on any node (even on the master node).

These two entities can live in a single binary or you can separate them.

- The Controller plugin is a gRPC server that can run anywhere. In terms of a Kubernetes cluster, it can run on any node (even on the master node).

These two entities can live in a single binary or you can separate them.

- Node Plugin

References

- Good example and explanation on how to implement CSI

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_qfSzrPn9Cs

- https://blogs.igalia.com/dpino/2016/04/10/network-namespaces/

- https://github.com/containernetworking/cni/blob/master/SPEC.md

- https://github.com/containernetworking/plugins

- show how the CNI works using the containetworking github.com account

- specification and implementation of CNI

- weavenet is network plugin for docker for variety of things (service discovery, etc), this website outlined how to use it as inside kubernetes

- Good explanation about how the different parts of Kubernetes works

Experimenting with Kubernetes

- A good guide on cloud provider

- Kubernetes on ARM (ODROID, RPi, Upboard combo)

- Kubernetes on ODROID N2

- Setting up a Multi-Arch, Multi OS cluster

- Kubernetes on Raspberry Pi: Challenges & Advantages

- Intalling kubernetes using kubeadm

- Kubernetes HA control plane

Books

- Programming Kubernetes - OReilly

- Kubernetes Patterns - OReilly

- Managing Kubernetes - OReilly